Copyright, Kellscraft Studio

1999-2002

(Return to Web Text-ures)

Children's Blue Bird

Content Page

Click Here to return to

the previous section

(HOME)

Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2002 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to Children's Blue Bird Content Page Click Here to return to the previous section |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

X

THE AWAKENING THE

grandfather's clock in

Tyl the woodcutter's cottage had struck eight;

and his two little Children, Tyltyl and Mytyl, were still asleep in

their little

beds. Mummy Tyl stood looking at them, with her arms akimbo and her

apron tucked

up, laughing and scolding in the same breath:

"I can't let them go on

sleeping till mid-day," she said.

"Come, get up, you little lazybones!"

But it was no use shaking

them, kissing them or pulling the bed-clothes

off them: they kept on falling back upon their pillows, with their

noses

pointing at the ceiling, their mouths wide open, their eyes shut and

their

cheeks all pink.

At last, after receiving a

gentle thump in the ribs, Tyltyl opened one

eye and murmured:

"What?....

Light?…Where are you?…. No, no, don't go

away…”

"Light!" cried Mummy Tyl,

laughing. "Why, of course, it's

light.... Has been for ever so long!… What's the matter

with you?… You look

quite blinded…"

"Mummy!... Mummy!" said

Tyltyl, rubbing his eyes. "It's

you!..."

"Why, of course, it's I!...

Why do you stare at me in that

way?… Is my nose turned upside down, by any chance?”

Tyltyl was quite awake by

this time and did not trouble to answer the

question. He was beside himself with delight! It was ages and ages

since he had

seen his Mummy and he never tired of kissing her.

Mummy Tyl began to be uneasy.

What could the matter beg Had her boy lost

his senses? Here he was suddenly talking of a long journey in the

company of the

Fairy and Water and Milk and Sugar and Fire and Bread and Light! He

made believe

that he had been away a year!...”

"But you haven't left the

room!" cried Mummy Tyl, who was now

nearly beside herself with fright. "I put you to bed last night and

here

you are this morning! It's Christmas Day: don't you hear the bells in

the

village?...."

"Of course, it's Christmas

Day," said Tyltyl, obstinately,

"seeing that I went away a year ago, on Christmas Eve!…

You're not angry

with meg … Did you feel very sad?... And what did Daddy

say?..."

"Come, you're still asleep!"

said Mummy Tyl, trying to take

comfort. "You've been dreaming!... Get up and put on your breeches and

your

little jacket ...."

"Hullo, I've got my shirt

on!" said Tyltyl.

And, leaping up, he knelt

down on the bed and began to dress, while his

mother kept on looking at him with a scared face.

The little boy rattled on:

"Ask Mytyl, if you don't

believe me.... Oh, we have had such

adventures!... We saw Grandad and Granny... yes, in the Land of

Memory... it

was on our way. They are dead, but they are quite well, aren't they,

Mytyl?”

And Mytyl, who was now

beginning to wake up, joined her brother in

describing their visit to the grand-parents and the fun which they had

had with

their little brothers and sisters.

This was too much for Mummy

Tyl. She ran to the door of the cottage and

called with all her might to her husband, who was working on the edge

of the

forest:

"Oh, dear, oh, dear!" she

cried. "I shall lose them as I

lost the others!... Do come!... Come quick..."

Daddy Tyl soon entered the

cottage, with his axe in his hand; he listened

to his wife's lamentations, while the two Children told the story of

their

adventures over again and asked him what he had done during the year.

"You see, you see!" said

Mummy Tyl, crying. "They have

lost their heads, something will happen to them; run and fetch the

doctor ....

"

But the woodcutter was not

the man to put himself out for such a trifle.

He kissed the little ones, calmly lit his pipe and declared that they

looked

very well and that there was no hurry.

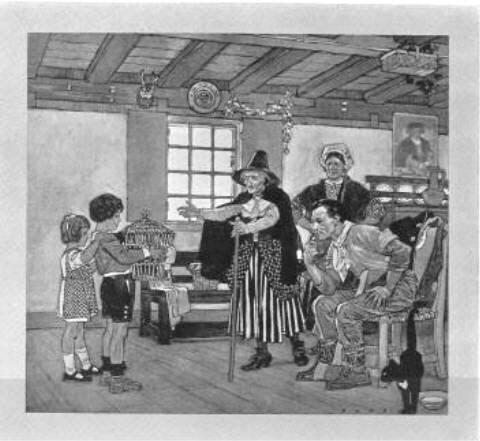

At that moment, there came a

knock at the door and the neighbour walked

in. She was a little old woman leaning on a stick and very much like

the Fairy Bérylune.

The Children at once flung their arms around her neck and capered round

her,

shouting merrily:

"It's the Fairy

Bérylune!"

The neighbour, who was a

little hard of hearing, paid no attention to

their cries and said to Mummy Tyl:

"I

have come to ask for a bit of fire for my

Christmas stew .... It's very chilly this morning .... Good-morning,

children.... "

Meanwhile, Tyltyl had become

a little thoughtful. No doubt, he was glad

to see the old Fairy again; but what would she say when she heard that

he had

not the Blue Bird? He made up his mind like a man and went up to her

boldly:

"It's the Blue Bird we were looking for! We have been miles and miles and miles and he was here all the time!" "Fairy

Bérylune, I

could not find the Blue Bird… "

"What is he saying?" asked

the neighbour, quite taken aback.

Thereupon Mummy Tyl began to

fret again: "Come, Tyltyl, don't you

know Goody Berlingot?"

"Why, yes, of course," said

Tyltyl, looking the neighbour up

and down. "It's the Fairy Bérylune."

"Béry... what?"

asked the neighbour.

"Bérylune,"

answered Tyltyl, calmly.

"Berlingot," said the

neighbour. "You mean

Berlingot."

Tyltyl was a little put out

by her positive way of talking; and he

answered:

"Bérylune or

Berlingot, as you please, ma'am, but! know what I'm

saying .... " Daddy

Tyl was beginning to have enough of it:

"We must put a stop to this,"

he said. "I will give them a

smack or two."

"Don't," said the neighbour;

"it's not worth while. It's

only a little fit of dreaming; they must have been sleeping in the

moonbeams....

My little girl, who is very

ill, is often like that...."

Mummy Tyl put aside her own

anxiety for a moment and asked after the

health of Neighbour Berlingot's little girl.

"She's only so-so," said the

neighbour, shaking her head·

"She can't get up... The doctor says it's her nerves... I know what

would

cure her, for all that. She was asking me for it only this morning, for

her

Christmas present...

She hesitated a little,

looked at Tyltyl with a sigh and added, in a

disheartened tone:

"What can I do? It's a fancy

she has...."

The others looked at one

another in silence: they knew what the

neighbour's words meant. Her little girl had long been saying that she

would get

well if Tyltyl would only give her his dove; but he was so fond of it

that he

refused to part with it....

"Well," said Mummy Tyl to her

son, "won't you give your

bird to that poor little thing? She has been dying to have it for ever

so long!

. .."

"My bird!" cried Tyltyl,

slapping his forehead as though they

had spoken of something quite out of the way. "My bird!" he repeated.

"That's true,! was forgetting about him!... And the cage!... Mytyl, do

you

see the cage?…It's the one which Bread carried... Yes, yes,

it's the same one,

there it is, there it is!"

Tyltyl would not believe his

eyes. He took a chair, put it under the cage

and climbed on to it gaily, saying:

"Of course, I'll give him to

her, of course, I will!..." Then

he stopped, in amazement: "Why, he's blue!" he said. "It's my

dove, just the same, but he has turned blue while I was away!"

And our hero jumped down from

the chair and began to skip for joy,

crying:

"It's the Blue Bird we were

looking for! We have been miles and

miles and miles and he was here all the time!... He was here, at

home!... Oh,

but how wonderful!... Mytyl, do you see the bird? What would Light

say?...

There, Madame Berlingot, take him quickly to your little girl.... "

While he was talking, Mummy

Tyl threw herself into her husband's arms and

moaned: "You see?... You see?.... He's taken bad again. He's

wandering…"

Meantime, Neighbour Berlingot

beamed all over her face, clasped her hands

together and mumbled her thanks. When Tyltyl gave her the bird, she

could hardly

believe her eyes. She hugged the boy in her arms and wept with joy and

gratitude:

"Do you give it me?" she kept

saying. "Do you give it me

like that, straight away and for nothing?... Goodness, how happy she

will be!...

I fly, I fly!... I will come back to tell you what she says.... "

"Yes, yes, go quickly," said

Tyltyl, "for some of them

change their colour!"

Neighbour Berlingot ran out

and Tyltyl shut the door after her. Then he

turned round on the threshold, looked at the walls of the cottage,

looked all

around him and seemed wonderstruck:

"Daddy, Mummy, what have you

done to the house?" he asked.

"It's just as it was, but it's much prettier."

His parents looked at each

other in bewilderment; and the little boy went

on:

"Why, yes, everything has

been painted and made to look like new;

everything is clean and polished.... And look at the forest outside

the

window!... How big and fine it is!... One would think it was quite

new!...

How happy I feel here, oh, how happy I feel!"

The worthy woodcutter and his

wife could not make out what was coming

over their son; but you, my dear little readers, who have followed

Tyltyl and

Mytyl through their beautiful dream, will have guessed what it was that

altered

everything in our young hero's view.

It was not for nothing that

the Fairy, in his dream, had given him a

talisman to open his eyes. He had learnt to see the beauty of things

around him;

he had passed through trials that had developed his courage; while

pursuing the

Blue Bird, the Bird of Happiness that was to bring happiness to the

Fairy's

little girl, he had become open-handed and so good-natured that the

mere thought

of giving pleasure to others filled his heart with joy. And, while

travelling

through endless, wonderful, imaginary regions, his mind had opened out

to life.

The boy was right, when he

thought everything more beautiful, for, to his

richer and purer understanding, everything must needs seem infinitely

fairer

than before.

Meanwhile, Tyltyl continued

his joyful inspection of the cottage. He

leant over the bread-pan to speak a kind word to the Loaves; he rushed

at Tylô,

who was sleeping in his basket, and congratulated him on the good fight

which he

had made in the forest.

Mytyl stooped down to stroke

Tylette, who was snoozing by the stove, and

said:

"Well, Tylette?….

You know me, I see, but you have stopped

talking."

Then Tyltyl put his hand up

to his forehead:

"Hullo!" he cried. "The

diamond's gone!... Who's taken my

little green hat?…Never mind, I don't want it any more!...

Ah, there's Fire!

Good-morning, sir! He'll be crackling to make Water angry!" He ran to

the

tap, turned it on and bent down over the water. "Good morning, Water,

good-morning!... What does she say?.... She still talks, but I don't

understand

her as well as I did.... Oh, how happy I am, how happy I am!..."

"So am I, so am I!" cried

Mytyl.

And our two young friends

took each other's hands and began to scamper

round the kitchen.

Mummy Tyl felt a little

relieved at seeing them so full of life and

spirits. Besides, Daddy Tyl was so calm and placid. He sat eating his

porridge

and laughing: "You

see, they are playing at being happy!" he said. Of course, the poor

dear

man did not know that a wonderful dream had taught his little children

not to

play at being happy, but to be happy, which is the greatest and most

difficult

of lessons.

"I like Light best of all,"

said Tyltyl to Mytyl, standing on

tip-toe by the window. "You can see her over there, through the trees

of

the forest. To-night, she will be in the lamp. Dear, oh, dear, how

lovely it all

is and how glad I feel, how glad I..."

He stopped and listened.

Everybody lent an ear. They heard laughter and

merry voices; and the sounds came nearer.

"It's her voice!" cried

Tyltyl. "Let me open the

door!"

As a matter of fact, it was

the little girl, with her mother, Neighbour

Berlingot.

"Look at her," said Goody

Berlingot, quite overcome with joy.

"She can run, she can dance, she can fly! It's a miracle! When she saw

the

bird, she jumped, just like that...."

And Goody Berlingot hopped

from one leg to the other at the risk of

falling and breaking her long, hooked nose.

The Children clapped their

hands and everybody laughed.

The little girl was there, in

her long white night-dress, standing in the

middle of the kitchen, a little surprised to find herself on her feet

after so

many months' illness. She smiled and pressed Tyltyl's dove to her heart. Tyltyl

looked first at the child and then at Mytyl: "Don't you think she's

very

like Light?'' he asked. "She is much smaller," said Mytyl.

"Yes, indeed!" said Tyltyl.

"But she will grow!..."

And the three Children tried to put a little food down the Bird's beak,

while

the parents began to feel easier in their minds and looked at them and

smiled.

Tyltyl was radiant. I will

not conceal from you, my dear little readers,

that the Dove had hardly changed colour at all and that it was joy and

happiness

that decked him with a magnificent bright blue plumage in our hero's

eyes. No

matter! Tyltyl, without knowing it, had discovered Light's great

secret, which

is that we draw nearer to happiness by trying to give it to others.

But now something happened.

Everybody became excited, the Children

screamed, the parents threw up their arms and rushed to the open door:

the Bird

had suddenly

But Tyltyl was the first to

run to the staircase and he returned in

triumph:

"It's all right!" he said.

"Don't cry! He is still in the

house and we shall find him again."

And he gave a kiss to the

little girl, who was already smiling through

her tears:

"You'll be sure to catch him

again, won't you?" she asked.

"Trust me," replied our

friend, confidentially. "I now

know where he is." You

also, my dear little readers, now know where the Blue Bird is. Dear

Light

revealed nothing to the woodcutter's Children, but she showed them the

road to

happiness by teaching them to be good and kind and generous.

Suppose that, at the

beginning of this story, she had said to them:

"Go straight back home. The

Blue Bird is there, in the humble

cottage, in the wicker cage, with your dear father and mother who love

you."

The Children would never have

believed her:

"What!" Tyltyl would have

answered. "The Blue Bird, my

dove? Nonsense! my dove is grey!... Happiness, in the cottage? With

Daddy and

Mummy? Oh, I say! There are no toys at home and it's awfully boring

there: we

want to go ever so far and meet with tremendous adventures and have all

sorts of

fun.... " That is what he would have said; and he and Mytyl would have set out in spite of everything, without listening to Light's advice, for the most certain truths are good for nothing if we do not put them to the test ourselves. It only takes a moment to tell a child all the wisdom in the world, but our whole lives are not long enough to help us understand it, because our own experience is our only light. Each of us must seek out

happiness for himself; and he has to take

endless pains and undergo many a cruel disappointment before he learns

to become

happy by appreciating the simple and perfect pleasures that are always

within

easy reach of his mind and heart. THE

END

|