| 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to Fairy Tales Content Page Click here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

| 1999-2003 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click

Here to return to Fairy Tales Content Page Click here to return to previous chapter |

(HOME) |

|

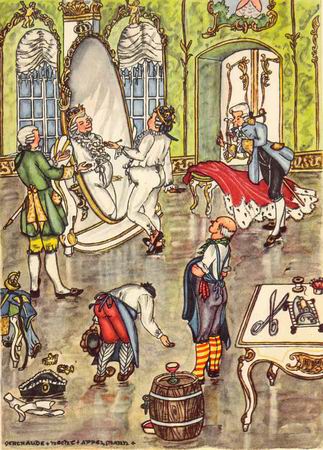

Many years ago there lived an Emperor who laid so great a value upon new clothes that he spent all his money on them in order to be smartly dressed. He did not care in the least about his soldiers, took no pleasure in theatre-going nor found a liking to drive into the wood, unless he could show off his new clothes. He had a robe for every hour of the day. and, as one says of a King “he is in his council.” so people always said: “The Emperor is in his dressing-room!” There was a merry life in the town where he lived. Plenty of strangers arrived daily, and one day there also came two swindlers. They pretended to be weavers, telling they knew how to weave the finest fabrics imaginable. Not only, they asserted, were the colours and patterns uncommonly fine, but the clothes, made of this stuff, would have the amazing quality to become invisible to any person being unfit for the office he holds, or unpardonably stupid. “Those would indeed be splendid clothes,” thought the Emperor. “By possessing them I should be able to find out which men in my realm are unfit for the position they occupy, and thus I could distinguish the wise men from the fools. Yes, no doubt. I must give them orders that stuff to be woven for me at once!” He handed the two swindlers a rich earnest that they should set to work. They also put up two looms, and feigned to work, but they had nothing at all on the loom. Nevertheless they called for the finest silk and the purest gold thread. But all this they put into their own bags working on the empty looms till late at night. “Now, I wonder how they are getting on with their stuff,” thought the Emperor, but he felt ill at ease at the idea that no person, whether silly or unfit for his post, might be able to see it. He believed, it is true, that there was no need to dread for himself, but thought he would send somebody else, though, to see how the matter was getting on. All the people in the whole town knew what peculiar power the stuff possessed, and everybody was eager to see how wicked or stupid his neighbour was. “I will send my old loyal minister to the weavers,” thought the Emperor, “he can best judge how the cloth looks, for he is clever, and no one fills his post better than he does!” So the good old minister went into the room where the two impostors sat working at the empty looms. “God bless me,” thought the old minister, opening his eyes wide. “In truth! I can’t see anything! But he was cautious enough to say so.” Both the swindlers begged him to step nearer, asking him if the patterns were not very pretty and the colouring beautiful. Thereupon, they pointed to the empty loom, and the poor old minister kept opening his eyes wide, but he was unable to see anything because there was nothing to see. “Goodness me!” thought he, “can it really be that I am so dull? I have never thought so, and nobody must know it! Am I not fit for my office? No, it won’t do to tell that I cannot see the stuff.” “Well, Sir, you don’t say anything about it?” asked one of the weavers. “Oh, it is so nice, most charming!” answered the old minister, peeping through his spectacles. “What a pattern and these colours! — Yes, I am going to tell the Emperor that both please me very much!” “Well, we are glad to hear that,” said the two weavers, and then they named the colours and explained the strange pattern. The old minister paid great attention to everything, that he might be able to repeat it to the Emperor on his return. And so he did. Now the swindlers demanded still more money, more silk, and more gold for weaving. They put all into their own pockets, and not a bit of thread was put at the empty looms as they did before. The Emperor presently sent again another able official to learn how the weaving was proceeding, and if the stuff would soon be ready. But he fared just as the first one, he gazed and gazed, but as, apart from the empty loom, there was nothing visible, he could not see anything else. “Is this not a pretty piece of stuff,” asked both the swindlers, showing and explaining the magnificent pattern that did not exist at all. “Stupid, certainly, I am not.” thought the man, “so it must be my office for which I am unfitted! That would be queer enough, but never give oneself away!” Therefore, he praised the stuff he did not see, and assured them of his joy about the beautiful colours and the exquisite design. “Yes, it is really most charming,” said he to the Emperor. Everyone in the town spoke of the magnificent stuff. Now the Emperor wanted to see it himself while it was still on the loom. With quite a host of selected men. among whom also were the two loyal officials who had been there previously, he betook himself to the two artful impostors, who were weaving now with all their might, but without any strand or thread. “Why, is that not splendid.” said both the honest officials. “May it please Your Majesty to have a look at the design and the colours?” And then they pointed to the empty loom, for they believed the other could doubtless see the cloth. “What?” thought the Emperor. “I see nothing at all. This is indeed frightful. Am I stupid? Am I not fit to be Emperor? This would be the worst that could ever befall me! Oh, it is very nice,” said he. “it meets with my highest approval,” nodding contentedly and inspecting the empty loom. He did not want to confess that he could see nothing. The whole suite that he had with him, gazed and gazed, but did not observe more than all the others. “However,” they said like the Emperor, “oh, that is fine!” And then they advised him to wear the new magnificent robes for the first time at the great impendent festival. “It is magnificent, pretty, excellent,” went from mouth to mouth and everybody seemed to be delighted with it. Each of the impostors was awarded an order of knighthood to be worn in their buttonholes, and the title of “Court Weaver”. The swindlers sat up all night long till the morning on which the feast was to take place, and they had lighted sixteen candles, so the people could see how hard they were working to get ready the Emperor’s new clothes. They feigned to take the stuff from the loom, cut it out in the air with big scissors, they sewed with needles without any thread, saying at last: “Look here, now the robes are ready!” The Emperor with all his illustrious officials went himself to both the impostors who raised up one arm just as though they were holding something, and said: “Look, these here are the trousers! This is the coat. that is the mantle,” and so on. “It is as light as a spider’s web, one might think one had nothing on the body, but that is the very beauty of it!” “Yes,” said all the functionaries, but they could not see anything, because there was nothing to see. “Will Your Imperial Majesty condescend to take off Your clothes.” said the swindlers, “then we may put on the new ones here in front of the large mirror!” The Emperor took off his clothes, and the impostors feigned to dress him in one garment of the new robes after the other, which were allegedly finished, and the Emperor turned round and round in front of the mirror. “Ah, how well they suit, how perfectly they fit,” said all. “What a design, what colours! They are showy robes!” “Outside they are standing with the canopy that is to be carried over Your Majesty,” announced the Grandmaster of Ceremonies. “Well, I am ready,” said the Emperor. “Don’t the clothes fit well?” and turned himself round again in front of the mirror, for he wanted to make believe as if he were examining his new robes closely. The chamberlains who were entitled to carry the train, bowed down so as to lift up from the floor with their hands. They strode along, and behaved as though they held something in the air. They dared not let it out that they could not see anything. Thus, the Emperor strode about under the gorgeous canopy, and all people in the street called out: “How matchless the Emperor’s new robes are! What a train he has to his robe! And how close it fits!” No one would let it appear that he saw nothing else, for he would have been unfitted for his post, or very stupid. No other clothes of the Emperor had brought about so much happiness as these ones. “But he has nothing on, though,” said a little child at last. “Hark! Listen to the voices of the innocent,” said the father. And one person whispered to the next one what the child had said. “Forsooth, he has nothing on at all,” at last shouted all the people. That stirred the Emperor’s mind, for the people to be right, but he thought to himself: “Now I must stand the test.” And the chamberlains walked on, carrying the train which did not exist at all.

Once upon a time there was a merchant who was so rich that he could pave with silver coins the whole street. and almost a small lane to boot. But he did not do so, he knew how to use his money otherwise. He never spent a penny without getting a shilling in return, so clever a merchant was he — until he died. Then his son inherited this money, and he lived a merry life, sought another pleasure every day, made kites out of bank-notes, and played, instead of with stones, with gold coins, flinging them into the water. Thus all his money could certainly be wasted. At last he had nothing more left than four pennies, and possessed no other clothes than a pair of shoes and an old dressing-gown. Now, his friends no longer cared for him, as they could not walk about the streets together. But one of them, who was good-natured, sent him an old trunk saying “Pack up!” Surely, that was a good piece of advice, but he had nothing to pack up. and so he seated himself in his trunk. It was a strange trunk, As soon as one pressed the lock, the trunk was able to fly. This was done by the man, and he at once flew off with his trunk high up through the chimney, over the clouds, farther and farther away. But whenever the bottom cracked a little, he felt alarmed that his trunk might burst to pieces. In this case, he would have made a remarkable somersault. Thus he got to the country of the Turks. He hid the trunk in the wood under withered leaves, and then went into the town. He could do that very easily, as with the Turks everybody would walk about like him, wearing a dressing-gown and slippers. Then he met a nurse with a baby. “I say, you Turkish nurse.” asked he, “what great castle is this so close to the town, and where the windows are put so high up?” “Here resides the King’s daughter,” replied the woman. “There is a prophecy that she will become very unhappy about a lover, and therefore nobody may come to see her unless the King and the Queen are present!” “I thank you,” said the merchant’s son, and then went out into the wood, seated himself in his trunk, flew on to the roof of the castle, and crept in at the window of the Princess. She lay sleeping on her sofa. So beautiful was she that the merchant’s son could not help kissing her. She awoke and was tremendously frightened. He said that he was the God of the Turks, and he had come down to the earth through the air. On hearing this, she was greatly pleased. Thus they sat side by side, and he told her stories of her eyes which were like the most splendid dark lakes, in which her thoughts floated like mermaids. And he went on telling her about her forehead which was like a snow-clad mountain with the most magnificent halls and paintings. And he told her about the stork which brings the lovely little babies. Surely, those were lovely stories. Then he wooed the Princess, and she instantly consented to marry him. “But you must come to see me next Saturday,” said she, “on this day the King and the Queen will be my guests for a cup of tea. They will be very proud when hearing that the God of the Turks is going to marry me. But just see to have ready a very pretty fairy-tale, for my parents love immensely to hear one. My mother would like it in the way of devotional meaning, and my father entertaining, so that one can laugh at it!” “Well, I shall bring no other wedding-gift than a fairy-tale,” said he, and then they parted. However, the Princess gave him a broad sword, which was studded with gold coins, and these he needed badly. Then he flew away, bought a new dressing-gown, and sat out in the wood, devising a fairy-tale. It should be ready by Saturday, and this seemed not to be so easy. He got it ready. and Saturday was come. The King, the Queen and the whole court were waiting for him at the Princess’ to take their tea. He was given a friendly reception. “Are you going now to tell us a fairy-tale,” said the Queen, “but such a one that is thoughtful and instructive?” “But such a one, too, that makes one laugh,” said the King. “Of course,” replied he and began to relate, “but now you must listen attentively!” “Once upon a time there was a bundle of matches which were utterly proud of their noble origin. Their pedigree, that is to say, the tall fir-tree of which each one was but a little bit of wood, had been a tall old tree in the forest. Now, the matches lay between the old tinder-box and an old iron pot, to which they told all about their youth. “In truth, at that time when we were a living tree,” they said, “we were really on a green branch! We had diamond-tea every morning and every evening, and this was the dew. Whenever the sun was shining, we enjoyed its rays all day long, and all the little birds could not forbear telling stories to us. Surely, we could feel rich as the trees with foliage were clothed only during the summertime, whereas our family possessed means enough for their green clothes both summer and winter. But one day, the wood-cutter came along, and our family was splintered to pieces. The head of our family got a post as a main-mast on a gorgeous ship which could sail round the world whenever it liked. The other branches got to different spots, and we now hold the office of kindling the light to all people. For this reason, we people of high rank have got into the kitchen!” “My fate has been shaped quite differently,” said the iron-pot by the side of which the matches lay. “From the very outset. ever since I came into the world, I have been scoured and heated. over and over again. I am the friend of the solid things, and I am the first one in this house. All my joy is to lie clean and tidy in my place, and to have a reasonable talk with my comrades. Except for the water-pail, which every now and then gets down to the yard, we always lead an indoor life. Our sole news-monger is the market-basket, which, however, talks too excitedly about the government and the people. Well, recently there was an old pot which, for fear of the abusive language he heard, fell down. and went to pieces, he was a noble-minded fellow, I assure you!” —“But now, you are talking too much,” interrupted the tinderbox, and the steel struck against the flint so that sparks were flying about. “Are we not going to spend a merry evening?” “Well, let us discuss who is the most aristocratic person of us,” said the matches. “No, I don’t like speaking of myself,” protested the earthen pot. “Let us arrange an evening-party! I shall start telling something that everyone of you has experienced. One can easily put up with it, and it is very pleasing. On the Baltic Sea near the beeches — ” “The is a nice beginning.” said the plates. “That will certainly be a story which pleases us well.” “Yes, I spent there my childhood with a peaceful family. The furniture was polished, the floors were scrubbed, and once a fortnight, new curtains were hung up!” “How well you know how to tell tales!” said the hair-broom. One can notice at once that it is a woman who relates. There is something pure that runs through it!” “Yes, one feels it,” said the water-pail jumping up with Joy, so that one heard it pattering down on the floor. The pot went on telling, and the end was as good as the beginning. All the plates clattered with joy. and the broom pulled some green parsley out of the sand-pit, and crowned the pot with a wreath of it because he knew that the others would be cross about it. “If I can crown him to-day,” he thought. “he is crowning me to-morrow.” “Now I will dance,” said the fire-tongs and began dancing. Heaven forbid, how was it possible for her to lift up one of her legs into the air! The old chair-covering, over there in the corner burst asunder on seeing it, “Shall I be crowned as well?” asked the fire-tongs, and so they crowned her. “They are but the rank and file,” thought the matches. Then it was the tea-urn’s turn to sing, but it had caught a cold, it said, and could not do so unless it were boiling. But that was only because it was conceited. It refused to sing except when it stood on the table in the family drawing-room. At the window there was an old quill pen with which the girl would write. There was nothing in particular about it, besides having been dipped too deeply into the inkpot, but it was just proud of it. “If the tea-urn will not sing,” it said. “ it can drop that. Outside there is a nightingale which knows how to sing, hanging in the cage. It has learned nothing. it is true. but we don’t care about that for this evening!” “I think it is most out of place.” said the tea-kettle — he was a kitchen-singer and step-brother to the tea-urn — that a strange bird is to be listened to! Do you call this patriotism? The market-basket shall pass its sentence.” “ I just worry,” said the market-basket, “I worry more than anybody can imagine! Is this a suitable way to spend the evening like that? Would it not be more reasonable to put all in order? Each one should get his place. and I should direct the whole game. That would be another thing!” “Let us make a noise,” said all. Then the door opened. It was the maid-servant, and now they stood still. No one moved. But there was not one pot which did not know its abilities, and how distinguished it was. “Surely, if I would have arranged it.” thought everyone to himself, “we might have had quite a merry evening.” The maid took the matches and kindled the fire with them. Behold! What sparks they emitted. and how they blazed up! “Well now, everyone can see.” they thought, “that we are the first. What splendour we have and what light we spread about!” Therewith they were consumed by the fire. “This was a magnificent fairy-tale,” said the Queen. “I quite imagine myself being in the kitchen with the matches. Well now, thou shalt have our daughter!” “Indeed,” said the King. “thou shalt get our daughter on Monday.” Then they said “thou” because he was now to be a member of the family. Now the wedding-day was appointed, and the evening before the whole town was illuminated. Biscuits and bretzels were distributed, and the street-boys shouted “hurrah” and whistled through their fingers. It was a wonderful spectacle. “Well, I think I must do something myself.” thought the merchant’s son, and bought some rockets, toy-torpedoes and all kinds of fireworks imaginable, put all into his trunk, and flew up into the air with them. In truth, this was no slight fuss! All the Turks jumped up, so that their slippers flew about their ears. Such a phenomenon in the air, they had never seen before. Now they could understand that it was the God of the Turks himself, who was to have the Princess. As soon as the merchant’s son came down with his trunk again in the wood, he thought: “I will walk into the town, to learn what impression it has made.” It was quite natural that he felt like it. What the people knew to tell one another, though! Everybody whom he asked about it, had watched it in a manner of his own, but all had thought it beautiful. “I myself beheld the God of the Turks,” said one, “he had eyes like shining stars and a beard like foaming water!” “He flew along in a fiery mantle,” said another. “The most charming angels’ heads peeped out of the folds.” Surely, he heard pretty things, and the next day he was to celebrate his wedding. Then he returned to the wood to seat himself in his trunk but where was it? The trunk was burnt to ashes. A spark from the fireworks had remained, the trunk had caught fire, and now lay in ashes. Now the merchant’s son was unable to fly any longer nor get back to his bride. She stood waiting on the roof all day long. She is still waiting, but he wanders all over the world telling fairy-tales. But they are no more so funny as the story of the matches he had related as a God of the Turks.

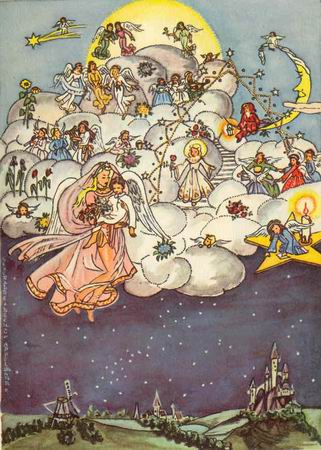

As often as a good child dies, an angel of God descends Heaven, takes the dead child in his arms, spreads out his white wings, and picks quite a handful of flowers, which he carries up to our Heavenly Father that they may bloom more beautifully there than they do on earth. Then God presses all the flowers to His heart, but He kisses the one that He likes best; and it gets a voice and is able to join in the chorus of bliss. Behold! All this was told by an angel of God carrying a dead child heavenwards, and the child listened to it as if dreaming; they flew over the abodes of the homeland where the little one had played, and passed through gardens of lovely flowers “Which of these shall we take with us and plant in the heaven?” asked the angel. Now, there stood a slender, delightful rosebush, but some wicked hand had broken the stem, so that all the branches, full of big, half opened buds hung withering round about. “Poor rosebush”, said the child. “Do take it away that it may bloom above in God’s realm!” And the angel took it up, kissed the child in return, and the little one half opened his eyes. They picked some of the rich gorgeous flowers, but gathered the disdained buttercup and pansy as well. “Now we have enough flowers”, said the child, and the nodded, but he did not fly upwards to God yet. It was night and quite still; they stayed in the big town, and hovered about one of the narrow lanes, where heaps of straw and ash resulting from people’s moving out, lay. There lay fragments of plates, pieces of plaster, rags, and old hats, and all this did not look well. Amidst all this confusion, the angel pointed down to some pieces of a flowerpot and to a lump of earth, that had fallen out of it. The earth had been held together by the roots of withered field flower which was good for nothing, and had therefore been thrown into the lane. “This one, let us take along with us,” said the angel. “I am going to tell you why while we are flying along.” They flew, and the angel told this story: “Down there, in that narrow lane, in a deep cellar, lived a poor, sick boy. Ever since his birth he had always been bed-ridden and, even when he felt at his best, he could only walk up and down the small room on crutches once or twice, that was all. During some days in summer, the sunbeams would even fall down into the very cellar for half an hour. Then the boy would sit there, lit up by the sun. watching the red blood shining through his delicate fingers which he held up before his face. Then people said: “This day, he has been out.” He knew the wood in its splendid spring-verdure only by his neighbour’s son bringing him the first bough from a beech-tree. This he held above his head, dreaming to stay in the beech-grove where the sun shone and the bird sang. One spring day, the neighbour’s boys brought him some field flowers too. Among them there happened to be one with the root, and therefore it was planted by him in a flowerpot and placed on the window-sill near his bed. The flower had been planted by a fortunate hand, it grew, put forth fresh shoots, and it was every year in full bloom. It became the sick boy’s most splendid flower-garden, his little treasure on this earth. He watered and tended it, and took care that it should enjoy every sunbeam, to the last one, which glided through the low window. The flower itself sympathized with his tears: for him alone it bloomed, only for him it spread its sweet fragrance, and delighted his eyes; towards the flower he turned in death when the Lord called him. One year he has now been with God, one year the flower has stood at the window, forgotten and withered, and has therefore been thrown out into the street when the lodgers left their house. And this is the same flower, the withered one, that we have added to our nosegay, because it is that flower that has rejoiced more than the richest in the garden of a queen.” “But how do you know all that?” asked the child whom the angel was carrying heavenwards. “I know it”, said the angel, “because I myself was once the little sick boy who hobbled on crutches; my own flower, I do know well!” The child opened its eyes altogether and looked into the angel’s glorious and cheerful face, and in the same moment they found themselves in that Heavenly Abode where joy and bliss prevail. God pressed the dead child to His heart, and it received wings like the other angel so that it could fly with him, hand in hand. And God pressed all the flowers to His heart: the poor withered field flower, however, did he kiss. And it received voice and carolled with all the angels hovering round the Almighty, some quite near, and others in great circles on and on, without end, but all equally happy. And they all sang, both great and small, together with the good. blessed child and the poor field flower that once had lain withered. flung down onto the heap of rubbish. on the day of the removal, in the narrow dark lane.

|