|

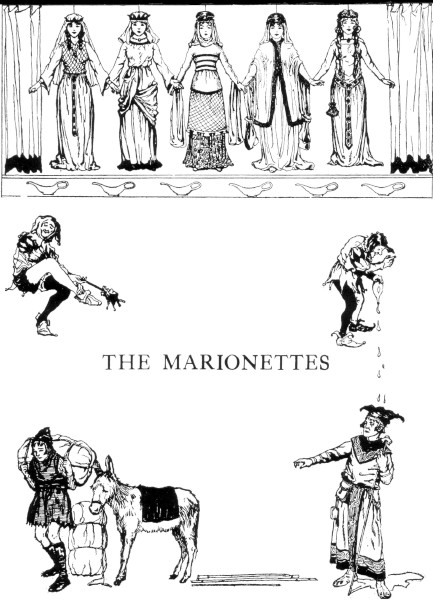

THE

MARIONETTES

After

the council comes the feast and then

Jongleurs

and minstrels, and the sudden song

That

wakes the trumpets and the din of war, —

But

now the Cesar's mood is for a jest.

Fellow

— you juggler with the puppet-show,

The

Emperor permits you to come in.

Ah,

yes, — the five wise virgins — very fair.

There

certainly can be no harm in that.

The

bride, methinks, is somewhat like Matilda,

Wife

of Duke Henry whom they call the Lion.

Aye,

to be sure — the little hoods and cloaks

All

tricked out with the arms of Saxony.

This

way — be brisk — now to the banquet-hall.

'Tis

clever — here come bride and bride-maidens

With

lights in silvern lanterns. Very good.

Milan

had puppet-shows, but none, I venture,

So

well set forth as this. . . . No Lombard here,

He

speaks pure French. Aha, the jester comes!

A

biting satire, yes, a merry jape, —

The

Bear that aped the Lion! A good song,

'Twill

please the Saxon, surely. Now, what next?

Here

come the foolish virgins all array'd

In

mourning veils, with little lamps revers'd.

The

merchant will not sell them any oil,

The

jester mocks them and the monk rebukes them, —

A

shrewd morality. Aye, — loyalty,

Truth,

kindliness and mercy, and wise judgment

Are

the five precious oils to light a throne.

A

pretty compliment, a well-turned phrase!

Woe

to the foolish Virgins of the Lombards

If

we find lamps unlighted on our way!

Then

surely will the door of hope shut fast

And

in that outer darkness will be heard

Weeping

and howling. . . . So, is that the end?

Hark,

fellow, you have pleased the Emperor,

This

ring's the token. Take a message now

That

may be spoken by your wooden King, —

The

master-mind regards all Christendom

As

but a puppet-show, — he pulls the strings,

The

others act and speak to suit his book, —

Aye,

truly, a most excellent puppet-show!

|

XVIII

THE

HURER'S LODGERS

HOW

THE POPPET OF JOAN, THE DAUGHTER OF THE CAPMAKER, WENT TO COURT AND

KEPT A SECRET

JOAN,

the little daughter of the hurer, sat on a three-legged stool in the

corner of her father's shop, nursing her baby. It was not much of a

baby, being only a piece of wood with a knob on the end. But the shop

was not much of a shop. Gilles the hurer was a cripple, and it was

all that he could do to give Joan and her mother a roof over their

heads. They had sometimes two meals a day; oftener one; occasionally

none at all.

If

he could have made hats and caps like those which he used to make

when he was a tradesman in Milan, every sort of fine goods would have

come into the shop. In processions and pageants, at banquets,

weddings, betrothals, christenings, funerals, on every occasion in

life, the people wore headgear which helped to make the picture. The

fashion of a man's hat suited his position in life. Details and

decorations varied more or less, but the styles very seldom did.

Velvet and fur were allowed only to persons of a certain dignity;

hats were made to show embroidery, which might be of gold thread and

jeweled. Merchants wore a sort of hood with a long loose crown which

could be used as a pocket. This protected the neck and ears on a

journey, and had a lining of wool, fur, or lambskin. Court ladies

wore hoods of velvet, silk or fine cloth for traveling. At any formal

social affair a lady wore some ornamental head-dress with a veil

which she could draw over her face. The wimple, usually worn by

elderly women, was a scarf of fine linen thrown over the head,

brought closely around the throat and chin, and held by a fillet. In

later and more luxurious and splendid times, the cone-shaped and

crescent-shaped head-dresses came in.

Hats

were not common in the twelfth century. The hair fell in carefully

arranged curls, long braids or loose tresses on the shoulders; the

face was framed in delicate veils of silk or sendal, kept in place by

a chaplet of flowers or a coronet of gold. Every maiden learned to

weave garlands in set patterns, and could make a wreath in any one of

several given styles, for her own hair or for decorating a building.

Red, green and blue were the colors most often used in dress, and on

any festival day the company presented a very gay appearance.

Gilles,

however, was obliged to confine himself to the making of hures or

rough woolen caps for common men. He had no apprentices, although his

wife and daughter sometimes helped him. His shop was a corner of a

very old building most of which had been burned in a great London

fire. It was the oldest house in the street and was roofed with

stone, which probably saved it. The ends of the beams in the wall

fitted into sockets in other beams, and were set straight, crooked or

diagonally without any apparent plan. Two or three hundred years

before, when the house was built, the space between the timbers had

been filled in with interlaced branches, over which mud was plastered

on in thick coats. This made the kind of wall known as "wattle

and daub." It was not very scientific in appearance, but it was

weather-proof. As there was no fireplace or hearth, the family kept

warm — when it could — by means of an iron brazier filled with

coals. Cooking — when they had anything to cook — was done over

the brazier in a chafing-dish, or in a tiny stone fireplace outside

the rear wall, made of scattered stones by Joan's mother.

Gilles

was a Norman, but he had been born in Sicily, which had been

conquered by the Norman adventurer Guiscard long before. He had gone

to Milan when a youth, and there he had met Joan's mother — and

stayed. The luxury of Lombard cities made any man who could

manufacture handsome clothing sure of a living. "Milaner and

Mantua-Maker" on a sign above a shop centuries later meant a

shop where one could find the latest fashions. Gilles was prosperous

and happy, and his little girl was just learning to walk, when the

siege of Milan put an end to everything. He came to London crippled

from a wound and palsied from fever and set about finding work.

They

might have starved if it had not been for a Florentine artist,

Matteo, who was also a stranger in London, but had all that he could

do. He lodged for a year in the solar chamber, as the room above the

shop was called. Poor as their shelter was, it had this room to

spare. Matteo paid his way in more than money; he improved the house.

He understood plaster work, and covered the inner walls with a smooth

creamy mixture which made a beautiful surface for pictures. On this

fair and spotless plaster he made studies of what he saw day by day,

drawing, painting, painting out and making new studies as he

certainly could not have done had he been lodged in a palace. All

along two sides of the shop was a procession of dignitaries in the

most gorgeous of holiday robes. In the chamber above were portraits

of the King and Queen, the Bishop of London, Prior Hagno preaching to

a crowd at Bartlemy Fair, some of the chief men of the government,

and animals wild and tame. He told Joan stories about the paintings,

and these walls were the only picture-books that she had.

Then

they sheltered a smooth-spoken Italian called Giuseppe, who nearly

got them into terrible trouble. He not only never paid a penny, but

barely escaped the officers of the law, who asked a great many

questions about him and how they came to harbor him. After that they

made it a rule not to take any one in unless he was recommended by

some one they knew. It was worse to go to prison than to be hungry.

One

day, when Gilles had just been paid for some work done for Master

Nicholas Gay, the rich merchant, a slender, dark-eyed youth with a

workman's pack on his shoulder came and asked for a room. Hardly had

Joan called her mother when the stranger reeled and fell unconscious

on the floor of the shop. He did not know where he was or who he was

for days. They remembered Giuseppe and were dubious, but they kept

him and tended him until he was able to talk. His tools and his hands

showed him to be a wood-carver, and his dress was foreign. His

illness was something like what used to be called ship-fever, due to

the hard conditions of long voyages, in wooden ships not too clean.

When

their guest was able to talk he told them that he was Quentin, a

wood-carver of Peronne. He had met Matteo in Messina and thus heard

of this lodging. He had come to London to work at the oaken stalls of

the Bishop of Ely's private chapel in Holborn. These stalls, or

choir-seats, in a Gothic church were designed to suit the stately

high-arched building. Their straight tall backs were carved in wood,

and the arm-rests ended in an ornament called a finial. Often no two

stalls were alike, and yet the different designs were shaped to fit

the general style, so that the effect was uniform. The carving of one

pair of arms might be couchant lions; on the next, leopards; on the

next, hounds, and so on. The seats were usually hinged and could be

raised when not in use. The under side of the seat, which then formed

part of all this elaborate show of decoration, was most often carved

with grotesque little squat figures of any sort that occurred to the

artist. Here Noah stuck his head out of a nutshell Ark; there a woman

belabored her husband for breaking a jug; on the next stall might be

three solemn monkeys making butter in a churn. Quentin's fancy was

apt to run to little wood-goblins, mermaids, crowned lizards, fauns,

and flying ships. He came from a country where the forests are full

of fairy-tales.

Joan

would be very sorry to have Quentin go away. She was thinking of this

as she sat in the twilight nursing her wooden poppet. When he came in

at last he had his tools with him, and a piece of fine hard wood

about two feet long. Seating himself on a bench he lit the betty lamp

on the wall, and laying out his knives and gouges he began to carve a

face on the wood.

Joan

could not imagine what he was making, and she watched intently. The

face grew into that of a charming little lady, with eyes crinkled as

if they laughed, and a dimple in her firm chin. The hair waved over

the round head; the neck was as softly curved as a pigeon's. The gown

met in a V shape at the throat, with a bead necklace carved above.

There was a close-fitting bodice, with sleeves that came down over

the wrists and wrinkled into folds, and a loose over-sleeve that came

to the elbow. The skirt fell in straight folds and there was a little

ornamental border in a daisy pattern around the hem. When the

statuette was finished and set up, it was like a court lady made

small by enchantment.

"There

is a poppet for thee, small one," Quentin said smiling.

Joan's

hands clasped tight and her eyes grew big and dark. "For me?"

she cried.

"It

is a poor return for the kindness that I have had in this house,"

answered Quentin brushing the chips into the brazier.

The

poppet seemed to bring luck to the hurer's household. Through Gilles,

Master Gay had heard of Quentin's work, and he ordered a coffret for

his wife, and a settle. The arms of the settle were to be carved with

little lady-figures like Joan's, and Master Gay asked if they could

not all be portraits of Princesses. Joan's own poppet was named

Marguerite for the daughter of the French King, who had married the

eldest son of Henry II. Quentin had copied the face from Matteo's

sketch upon the wall, and in one room or the other were all the other

members of the royal family. But as it would not be suitable to show

Queens and Princesses upholding the arms of a chair in the house of a

London merchant, Quentin suggested that they change the design, and

use the leopards of Anjou for the arms, while the statuettes of the

Princesses were ranged along the top of the high back. There could be

five open-work arches with a figure in each, and plain linen-fold

paneling below. Where the carving needed a flower or so he would put

alternately the lilies of France and the sprig of broom which was the

badge of the Plantagenets. Thus the piece of carving would

commemorate the fact that the family of the King of England was

related to nearly every royal house in Europe through marriage. It

would be a picture-chronicle.

In

the middle arch was Marguerite, who would be Queen of England some

day if her husband lived. At her right hand was Constance of

Brittany, wife of Geoffrey, who through her would inherit that

province. The other figures were Eleanor, who was married to Alfonso,

King of Castile; Matilda, who was the wife of Henry the Lion, Duke of

Saxony, the most powerful vassal of the German Emperor; and Joan, the

youngest, betrothed to William, called the Good, King of Sicily.

"There

will be two more princesses some day," said Joan, cuddling

Marguerite in her arms as she watched Quentin's deft strokes. "Prince

Richard is not married yet, and neither is Prince John."

"The

work cannot wait for that, little one," Quentin answered

laughing. "Richard is only sixteen, and John still younger. Yet

they do say that the King is planning an alliance with Princess Alois

of France for Richard, and is in treaty with Hubert the Duke of

Maurienne for his daughter to wed with John. I think, myself, that

Richard will choose his own bride."

Joan

said nothing, but in her own mind she thought it would be most

unpleasant to be married off like that, by arrangements made years

before.

"The

marriage with Hubert's daughter," Quentin added half to himself,

"would keep open the way into Italy if it were needed. It is a

bad thing to have an enemy blocking your gate."

Although

her poppet was carved so that the small out-held hands and arms were

clear of the body, and dresses could be fitted over them, Joan found

that there were but few points or edges that were likely to be

chipped off. The wood was well seasoned, and the carving followed the

grain most cunningly. Neither dampness nor wood-boring insects could

easily get into the channels where sap once ran. This was part of the

wisdom of wood-carving.

When

Joan grew too old to play with her poppet she sometimes carried her

to some fine house to show a new fashion, or style of embroidery.

Marguerite had a finer wardrobe than any modern doll, for the little

hats, hoods and head-dresses had each a costume to go with it, and

all were kept in a chest Quentin had made for her, with the arms of

Milan on the lid. No exiled Milanese ever quite gave up the hope that

some day the city would be rebuilt in all its splendor, and the

foreign governors driven from Lombardy. Joan used to hear her father

talking of it with their next lodger, Giovanni Bergamotto, who was a

peddler at fairs. Gilles had had steady work for a long time, and was

making not only the rough caps he used to make, now turned out by an

apprentice, but fine hats and caps for the wealthy. A carved and

gilded hat swung before the door, and Joan learned embroidery of

every kind. She saw Quentin now and then, and one day he sent word to

her, by the wool-merchant Robert Edrupt, that Queen Eleanor wished to

see the newest court fashions, and that Joan might journey with

Edrupt and his wife to the abbey where she was living. It was one of

the best known houses in England, and the Abbess was of royal blood.

It was not at all unusual for its guest-rooms to be occupied by

Queens and Princesses.

Quentin

had been sent there to do some work for the Abbey, and in that way

the Queen, through Philippa, her maid of honor, had heard of Joan.

"I

suppose it is a natural desire in a woman," Master Edrupt said

when they talked of the matter, "but somehow I would stake my

head it is not the fashions she is after."

Barbara

his wife smiled but said nothing. She agreed.

When

Joan had modestly shown her wares, and the little wooden court lady

had smiled demurely through it all, the Queen dandled Marguerite on

her knee and thoughtfully looked her over.

"The

face is surely like the Princess of France," she said. And Joan

felt more than ever certain that there was a reason for this interest

in poppets.

Later

in the day she found out what it was. Quentin was carving other

little lady-figures like those he had made years ago for Master Gay.

He had also made the figures of a Bishop, a King, a Monk, and a

Merchant; with a grotesque hump-backed hook-nosed Dwarf for the

Jester. It looked as if a giant were about to play chess. Padraig, an

Irish scribe who had made some designs for the Queen's

tapestry-workers, was using his best penmanship to copy certain

letters on fine parchment. Giovanni, who had sprung up from

somewhere, was making a harness-like contrivance of hempen cords,

iron hooks and rods, and wooden pulleys. When finished it went into a

small bag of tow-cloth; if stretched out it filled the end of a rough

wooden frame. Joan began to suspect that the figures were for a

puppet-show.

"It

is time to explain," Quentin said to the others. "We can

trust Joan. She is as true as steel."

Joan's

heart leaped with pride. If Milan had only honor left, her children

would keep that.

"It

is this, Joan," Quentin went on kindly. "In time of war any

messenger may be searched, and we do not know when war will come.

King Henry desires above all things the peace of his realm. He will

not openly take the side of the Lombard cities against Frederick

Barbarossa — yet. But he will throw all his influence into the

scale if he can. The Queen has hit upon a way by which letters can be

sent safely to the courts of Brittany, France, Castile, Sicily, and

even to Saxony, which is in Barbarossa's own domains. Giovanni will

travel as a peddler, with the weaver-boy Cimarron as his servant or

companion, as may seem best. He will have a pack full of such pretty

toys as maidens love, — broidered veils, pomanders, perfumed

gloves, girdles — nothing costly enough to tempt robbers — and

these wooden poppets of ours. We cannot trust the tiring-women in

times like these, but he may be able to give the letters into the

hands of the Queens themselves. No one, surely, will suspect a

poppet. These gowns and wimples will display the fashions, and I had

another reason for telling you to bring them all. If he cannot get

his chance as a peddler he can hang about the court with a

puppet-show. Now, look here."

Quentin

took the softly smiling poppet and began to twist her neck. When he

had unscrewed the dainty little head a deep hole appeared in the

middle of the figure. Into this Padraig fitted a roll of parchment,

and over it a wooden peg.

"May

she keep it?" Quentin asked gently. "There is need for

haste, and I have not time to make another figure."

Joan

swallowed hard. Marguerite had heard many secrets that no one else

knew. "Aye," she said, "I will let her go."

Then

each little figure in turn received its secret to keep, and Joan,

Lady Philippa, and the other maids sewed furiously for a day and a

half. Each Princess was gowned in robes woven with the arms of her

kingdom. The other figures were suitably dressed. The weights which

made the jester turn a somersault were gold inside a lead casing —

Giovanni might need that. There were jewels hidden safely in his

dagger-hilt and Cimarron's, but to all appearance they were two

common chapmen. They were gone for a long time, but Marguerite —

the only poppet to return — came back safely, and inside her

discreet bosom were letters for the King. Cimarron brought her to the

door of Gilles the hurer, and told Joan that Giovanni, after selling

the puppet-show, had stayed in Alexandria to fight for Milan.

|