(Return to Web Text-ures)

Click Here to return to

Our Servian Cousin

Content Page

(Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to return to |

CHAPTER III

THE TWO SLAVAS

THE days passed on quite merrily, but uneventfully, with their regular round of duties. As usual, the women were far busier than the men. Militza now helped in making the earthenware crockery used in the house. This was done by digging out some potter's clay, pounding it with an axe, adding goats' hair, and, after pouring on hot water, moulding the paste with the hands. The rim was always first drawn out, then the pot was shaped. Cold ashes were next strewn over it, to absorb the moisture, and, lastly, the vessel was placed in live coals, covered with ashes, and left until morning, when it was ready for use.

Whenever the work grew irksome there was always a holiday to which to look forward. The most important to Dushan's family was the day of their patron saint. Every Servian family has a patron saint, and the fete in his honor is so universal an event that it is generally spoken of merely as Slava, the celebration, or Slaviti, to celebrate.

For a whole week before this the family fasted. The house was given an especial cleaning that all might be of spotless purity in the saint's honor. This included the large kitchen, which was very neat, the woodwork being all planed, the benches always washed very clean. In this kitchen there was a square, low hearth, with a wide, open chimney in which hams and dry salted pork and beef were hanging, and on the beams of which were suspended chains for various cooking vessels. Most of the baking was not done here, but in a special oven in the courtyard adjoining. There was also a sitting and dining room, with crude religious prints on the wall, and a wooden panel, with the image of the household saint, before which a small oil lamp was suspended.

A bedroom opened out from this, the floor covered with a bright, home-made carpet. Underneath the house was a cellar, which now had barrels of wine and a special kind of brandy, made of plums; but, in winter, also served as a store-house for vegetables. Back of the gardens were the sheds for the domestic animals, and a big granary for grain.

On the morning before the Slava day, Militza gathered a big bouquet of iris, called perunica after the old Slavic pagan god, Perun, ruler of thunder and lightning. There was probably no garden in the entire village without the iris, nor any house on whose roof did not grow the choovar-kutya, or house guardian, a plant believed to protect the home from lightning strokes.

"I know you like these," Militza remarked to her smiling mother, as she placed the bouquet on a table in the sitting-room, in an earthenware vase made by herself. She then accompanied her mother through the rooms in the last round of inspection that nothing should have been left undone, for guests were to begin arriving that afternoon.

In the meantime, Dushan and his father had come in. They had had scarcely time to dress themselves in their best, as Militza and her mother had already done, when the first visitor announced himself with the shout: "Oh, master of the house, are guests welcome?"

Dushan's father hastened forward with hand outstretched. "Certainly," he responded, "such good guests as you are."

It would have been quite curious to us to see these men embrace and kiss, the visitor remarking as he handed an apple to his host, "May your Slava be happy!" And the host responding, "And may your soul be content before the Father Almighty."

This first guest was a tall, lean man with a grave face, bronzed by the sun. He was Dushan's koom, or godfather, and had been the principal witness at the wedding of Dushan's parents. This koomship is considered a very sacred relationship in Servia, and, as the other members of the family came forward, their greeting testified to the esteem in which the man was held.

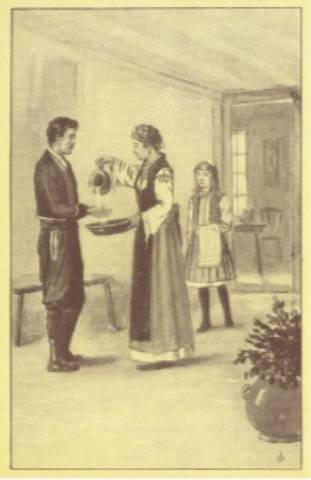

"The water was poured over the hands"

He was followed by other guests, who each brought a fruit of some kind, and then, after certain ceremonies and prayers had been observed, supper was announced. Militza's mother first carried around a basin and a pitcher of water, that each guest might wash his hands, for no Servian would think of sitting down to a meal without having done so. The water was poured over the hands, which were held above the basin, not in it. Militza followed her mother with a finely embroidered towel. This duty performed, they all placed themselves at low tables, and the host began to serve his guests. It was not until next day, however, that the celebration, partly social, partly religious, was in full swing. Everybody who met Dushan's father now saluted him with the words, Sretna Slava (A happy fete), and a cordial handshake, and the children shouted the same to Dushan and Militza.

A large number of friends accompanied the family to church. No sooner were the services ended, than some one, outside, started to play one of the national dances, and brisk dancing took place.

Many of the younger folks remained to dance all day. Others went to Dushan's home, where a big mid-day meal awaited them, the principal dish of which was a roast of lamb. There was also an especial Slava cake, which had been consecrated in the church, passed to each guest. The upper surface was divided by a cross into four sections, each one of which bore the initials of the words: "Jesus Christ, the Victor." But the eyes of the children fastened themselves more particularly on what is called the Kolyivo, or sacrifice. This was formerly something killed with a knife, but now consists of boiled wheat, walnuts, and almonds sweetened with powdered sugar and piled up and decorated with colored frosting.

Throughout the day the Kolyivo, and a kind of fruit preserve called Slatko, were passed, together with coffee, to every guest. There was much singing and frequent firing of pistols--a Servian way of giving vent to pleasant excitement. When, finally, the koom began to recite some of the national songs describing the brave fights of Servian heroes with Turkish oppressors, all drew their chairs nearer and listened with a rapt attention which showed that, old as the stories were, they were very, very dear to the hearts of the hearers.

But, if this Slava was an important one to a single family, there was another which was of equal interest to the entire village, the celebration of the village's patron saint. This fell late in June, just after the close of school for vacation.

For several days before, great preparations were made for the event, which was to be followed by a picnic in the woods near the church. The children could hardly contain themselves with excitement. Fifty or sixty sheep were killed. In every house there was much baking, particularly of bread. This was made by placing the dough into a certain kind of earthenware dish, covering it with embers, and baking slowly.

It was only five o'clock when Militza awoke on this Slava morning.

"Dushan! Dushan! get up," she shouted. "It's Slava day!"

Dushan did not have to be called. By six both children were busy helping their parents pack the things to be taken. These included five big loaves of bread, and several jars of home-made wine in wicker baskets.

By nine o'clock the streets were filled with village folk on their way to the church. There, a procession was formed, with a strong young man, carrying a wooden cross, at the head. Behind him came the priest with the Gospels, and several peasants, two by two, bearing holy pictures, called Ikons. Other peasants followed with their hats in their hands. When the procession reached a lime tree which marked one of the boundaries of the village, and on which a cross had once been cut, it stopped, and men, women, and children fell to their knees while the priest, with appropriate ceremonies, renewed the cross. Any tree so marked was considered sacred. It was a sin to break its branches, or even to throw a stone into it.

"By nine o'clock the streets were filled with village folk."

This ended the purely religious side, and now came the merrymaking part, beginning with the firing of pistols. The place chosen for the picnic was in a little clearing, in a near-by grove of lime and wild pear trees, which was soon reached, and where every one immediately began to work, the children gathering twigs for the fires, the older boys splitting wood, and preparing places on which the sheep were to be roasted whole.

Before these were ready to be eaten, the little girls and boys ran into the forest to gather strawberries and raspberries, which were very plentiful. There was a good-natured rivalry displayed in trying to gather the most. Militza especially exerted herself, and, when she found that two of her companions had outdone her, she felt so chagrined that the tears began to gather in her eyes.

Just then a light step was heard behind her. It was Yovan, separated for once from his mate. He took in the situation at a glance and, bending over, spoke to the child. There was always something peculiarly comforting in the name "Little Sister," which he gave her.

"Little Sister," he now whispered, "remember the saying, 'A middling good luck is the best.'" The next instant he had skipped away, boy fashion; but Militza's face had cleared.

So, after all, it was a merry lot of little girls that danced up with baskets of berries to where their mothers and older sisters were spreading table-cloths and piling pyramids of bread in the center of each.

And how much all did eat when at last the sheep were ready to be served, and all had placed themselves, cross-legged, around the tables! Dushan and Militza sat next to an older brother who had been married only a few months before. His wife, according to custom, addressed her little sister-in-law and brother-in-law with most endearing names, calling Militza most often "My blue iris," and Dushan "pigeon" or "hero."

At the conclusion of the meal, one person after another burst into song. Some of the songs chosen were the national airs: others were entirely impromptu.

Then an old peasant took up his bagpipe and, at the signal, two couples jumped up and danced a peculiar dance which consisted of shakes of the head and clapping of hands as well as movement of the feet.' Most of the girls wore several rows of silver coins around their necks, and these added a pleasant tinkling sound to the drone of the bagpipe music. Every now and then one of the men gave expression to his joy by shouting out a few verses --often very saucy ones w composed on the spur of the moment.

It would be tedious to relate all the games played, all the stories told, all the jokes perpetrated, and all the songs sung by the merry party before the hour of departure. As that neared, the company gathered in a cluster and spontaneously joined in the patriotic song of all the Servians, "Onamo! Onamo!" written by the present talented King of Montenegro.

Click the

icon![]() to continue to the next chapter of Our Servian Cousin.

to continue to the next chapter of Our Servian Cousin.