| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to

return to Florida Trails Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

| Copyright, Kellscraft Studio 1999-2004 (Return to Web Text-ures) |

Click Here to

return to Florida Trails Content Page Click Here to return to last Chapter |

(HOME) |

|

CHAPTER

XVI

ONE ROAD TO PALM BEACH One of the Alice-in-Wonderland fruits of the pineapple ridge which lies to the westward of the Indian River is the papaw. I never see it but I expect to find the walrus and the carpenter sitting under it engaged in animated argument. Especially is this the case with one variety, imported, they tell me, from the West Indies. Here is a stalk that comes up out of the ground as a milkweed might, green and succulent till it over-tops a man’s head, spreading from this single stem somewhat milkweed-like leaves from four to eight inches long. Nodding from the axils of these leaves come the flowers, followed by the fruit which is the grotesque climax of the whole, for here, stuck close on this succulent, head-high stem, is a muskmelon, or something just as good, so far as appearance goes. The thick, green rind becomes yellow on ripening and even when you twist the fruit off and hold it in your hand the muskmelon thought remains uppermost. You may taste this goblin-land muskmelon if you will and stilt not entirely lose the idea, though it is to me something like eating a muskmelon in a bad dream. There are people who say they like papaws, and that if you take them at just the right period of their ripeness and eat them muskmelon-wise with sugar and a spoon you will hardly know the difference. Such people may have all the papaws that have thus far been reserved for me. Well out in the pine barrens, I find another shrub which is a close relative of the papaw, the custard apple. This is a wild fruit which I am quite prepared to believe is delicious, perhaps because I have never eaten it. The opossums, coons and foxes, all very fond of it, have gotten ahead of me, long ago, and since their harvesting the low-growing shrub has been but a leafless thing, not to be noticed in a world of tropic vegetation. Now creamy white blossoms have burst from the bare twigs and are sending a new fragrance all along the level barrens on the soft, summer breeze. This fragrance has in it something of orange blossoms, something of the fruity odor of the guava which is to some people unpleasant but which I declare delicious, and a wild delight of its own. It suggests things good to eat. Some perfumes give you dreams of disembodiment in heavenly spaces of pure delight. Of such are carnations and English violets, the clethra of our Northern swamps and the wild cherokee roses of the Southern hedgerows. The odor of the custard apple blooms makes you think of banquets of delicious fruits served by pink-fleshed, round-bodied wood nymphs while amorous breezes blow soft from Southern seas. The newborn scent of the custard apple blooms has added a zest to the joy of the morning breezes. These were sufficiently intoxicating before. Always there are odorous flowers in bloom here, and always there is the spicy fragrance of the long-leaved pines to form a basis for any delight which they may bring. The soft winds which are their messengers call you out mornings early and I do not wonder that this is never a land of the closet or the counting house. No one whose senses are set a-tremble by them can stay indoors, and once lie is afoot they lead him on and on, nor does nightfall make him willing to return. Then the great white moon simply lends further enchantment to the road. To-day this lure led me far out on the old Government trail which is now, strange to relate, one road to Palm Beach. This is one rarely traversed by the butterflies of fashion. You may see these gliding by on the Pullman limited, looking with road-weary, unseeing eyes through the thick glass of the windows. The yachts of others take them down the sparkling waters of the Indian River, but now and then an automobile enthusiast, lured south by the good trails through Ormond and Daytona and Rockledge, then bewildered by the vast sand depths of the roads below and finally learning with sinking heart at Fort Pierce that there is no bridge across the St. Lucie nearer its mouth, swings westward into the limitless prairie and follows this old Government trail which swings out from the noise of breakers somewhere above the head waters of the St. Lucie, keeps for a dozen to a score of miles to the westward of the seacoast, and marches steadily southward to Miami. I doubt if the country along its two shallow ruts is any less wild to-day than it was in the days of Osceola. Except for those narrow ruts which you may not see two rods away man has left the region unmarked. You see there what Ponce de Leon may have seen.

A mile west of the St.

Lucie you still carry the settlements with you. Here are ditches, that

first requisite of Florida farming, and wire fences, which come next.

Here are comfortable houses, set high on heartwood posts, and here too

are groves of grapefruit trees, the great golden globes weighing the

tough branches with their glossy, dark-green foliage to the ground.

Here are dogs that bark and cocks that crow and all the simple, genial

activities of farm life. You go your mile and with the houses at your

back you stand within the untamed wilderness. A mile farther and you

may look which way you will and you are lost from all touch with man.

But before you make the mile you will pause and turn, for there, upside

down upon a tree, but with an arrow pointing due south, is a sign which

says, “To Miami”. The last warning, guiding word of civilization is

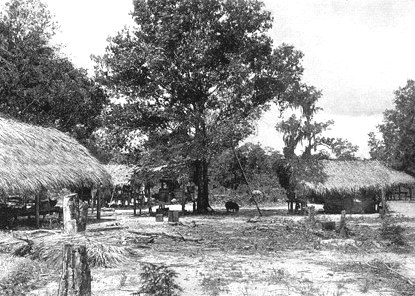

humorous and you plod southward into the primeval with a laugh.  A Seminole village deep in the flat woods of Southern Florida After a little the spaces take you in and make you one with their fraternity. The sun and the wind spy upon you. The broad blue eye of the heavens looks you through and finds you fit. Thereafter you begin to see this barren, lonely world as it is, and find it neither barren nor lonely. The absolute level begins to show undulations, and after you have walked it a half-score of miles you may tell the hills from the valleys though the variation be but that of a half-foot in a quarter section. Here is the top of a ridge which you might need a theodolite to find if it were not that it has its own peculiar vegetation. Along this the taller pines have crept and found permanent foothold. With them have come the saw palmetto, accentuating the rise of inches by the dense green vegetation of a foot or two in height. No summer floods have long topped this ridge, else the palmettos had failed to find permanent rooting here. Down its long slope they fall away, and though the pines have ventured farther than they, the water has dwarfed them at first and later left them but dead stubs a few inches in diameter and standing but a score or so of feet high. A study of them will show you not only the swing of the land from high to low, but the swing of the seasons through wet to dry and back again. During long successions of droughty years the pines have seeded down the slope and made a small growth in the rich bottoms. Then the pendulum of annual rainfall has swung back again and a series of wet decades have followed. Through these the trees have failed in growth and died, with their roots under water. Now their bareback, white stubs stand as markers on the borders where prairie land runs into muck. On the intervals of prairie grow the grasses, soft, brown and ripe with last year's growth, showing as yet but little of the green of this. These paint all the background of the scene with their olives and tans, as if the painter oŁ it first made his background with grass, then set his figures and lights and shades upon this, the gray stubs, the deep brown trunks of living trees, the vivid green of the palmetto leaves and gold of sunlight and purple of shadows chasing one another over all. The high lights in all this scene are the pools. Where the long dip of the land culminates the grasses give way to sedge and bulrush, and these to sparkling water which catches the shine of the wide sky and throws it back to the eye in silvery lights. Such, in broad splashes of color, is the prairie through which this old Government trail winds, from the St. Lucie to Palm Beach, and on down to Miami. Always the pines are present, though seemingly always just beyond. They stand so far apart that all about you is invariably the open space, while beyond, dwindling into the distance of receding miles, the trees draw together and group in a forest that you are never to find. As you proceed it recedes, slipping away in front and closing in behind as if the trees, shy but curious, fled, then followed. By the time you see all this the wide spaces are no longer lonely, and the individuals that inhabit them begin to step forward out of the mass and salute you. I always notice first the prairie flowers. Like the trees these are scattered here and there, the conspicuous ones in no wise as plentiful as the daisies and buttercups of Northern meadows. Scattered like big stars at twilight the heliopsis blooms show golden disks of composite flowers, veritable tiny suns in the prairie firmament, while about them revolve constellations of yellow stars of coreopsis. The ground in moist spots is often salmon red with the plants of the sundew and starred yellow with the blooms of the tiny, land-born utricularia, while in the pools their larger, many-flowered brethren float free, touching heads almost and studding the pool as stars stud the sky on a moonless, winter night. Only in the pools is this profusion to be found. In some of these the blue blooms of the pickerel weed crowd shoulder to shoulder, almost as close as in some Northern bogs I know. But the flowers of the drier, grassy plains are far more scattered. Indeed, one may walk a half mile sometimes and hardly see one. Again they are more numerous but never what might be called grouped. And yet, I must needs revise that again. There are places where the moist ground is white with Houstonia rotundifolia, which is not so very different from Houstonia coerulea, the common bluet of our Northern May fields. In other spots the purple-flowered variety, Houstonia purpurea, is very plentiful; yet neither have I found making such solid masses of bloom as the Northern variety. Of all the varied flowers of these sky-bounded levels, however, the one that pleases me most is the Calopogon. It makes the beautiful, level wilderness more beautiful with the quaint racemes of bright purple, curiously constructed flowers. I think the most conspicuous bird along this lone, level trail is the black vulture, which in this region seems to be more common than the turkey buzzard. It is not always easy to distinguish the two at a distance, but the vulture has shorter wings, is a heavier bird, flaps oftener in flight and the under sides of his wings are silvery. In places where the young grass is springing beneath still growing pines I find the Florida grackle, which is hardly to be told from our Northern species, in numbers, feeding on the ground and singing and fluttering iridescent black wings in the trees. With the blackbird groups fly up flocks of a swifter, cleaner built bird, colored in the main a slaty gray. These birds have the unmistakable head of the dove, and my first thought on seeing a flock of them was that I had stumbled upon a remnant of that vanishing bird, the passenger pigeon. This was a smaller bird, however, and, nowadays, a far more common one, the mourning dove. The whistling of their wings on first starting into flight should have told me better, for the flight of the passenger pigeon is said to be noiseless. The mourning dove is a beautiful bird, with those gentle outlines which make all birds of this species lovable, but for quaint, gentle beauty it has a rival in the ground dove which is quite as common here. These I find in the open prairie or among the pines, but far more often in the scrub of the palmetto hammocks, where they run along the ground almost at my feet, gentle, lovable and unafraid. The bird seems to be as much like a quail as a dove as its feet twinkle over the grass. In flight it is like a picture on a Japanese screen. But, after all is said and done, the loveliest bird I have seen in all the South, pine barrens or savannas, palmetto hammocks or village gardens, is the bluebird. Here and there these may be found all along the Palm Beach road, sitting perhaps on top of the gray bones of a dead prairie pine with the rich cinnamon red of the breast and throat turned to the sun, or dropping thence like a bit of the blue sky itself, fluttering down into the olive brown wire grass, seeming to add a more beautiful bloom to the prairie than I have yet found there. The faint carol of the bird is so slight a sound that it might well be lost in all this limitless space, but somehow it seems to carry far and is sweeter than any song of Southern bird that I have yet heard. When the bluebird goes North the savannas will have lost their finest touch of beauty and of charm.

To those who would see the

real Florida I recommend this lone Palm Beach trail, not taken in the

whirl of an automobile rush to safety under the wing of one of the big

hotels, but slowly and with open eyes and ears that the beauty and

significance of the place may enter in. Chief of these, I fancy, and

longest to be remembered will be the wide sweep of sky which there

seems to bend nearer and be bigger, bluer and friendlier than in most

other places. The southeast trade winds sweep across this sky all day

long, and bring with a temperature of June great store of white clouds

that now roll in cumulus heads and again are torn to white streamers of

carded fleece. Sometimes these gather and darken and spill April-like

showers for a moment, then blow over and leave the vivid sun to pour

the round, inverted bowl of the sky full of the sunshine's gold.

Through it all you walk as if on the pinnacle of the world with the sky

very big and very near and all things friendly. |